Living Land Acknowledgement Statement

PAFA is moving to craft an official territorial acknowledgement for the institution.

Follow this process below

Our Commitment to Reconciliation and Healing

The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) is located in Lenapehoking, the unceded homeland of the Lenape Peoples. Due to ongoing colonization and land swindles like the Walking Purchase of 1737, in which Pennsylvania authorities forcibly removed Lenape Peoples from this land, many Lenape communities currently live in diaspora outside of their homeland.

These Lenape nations include the Delaware Nation in Anadarko, Oklahoma; the Delaware Tribe of Indians in Bartlesville, Oklahoma; the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians in Wisconsin; the Munsee-Delaware Nation in Ontario; the Delaware Nation at Moraviantown in Ontario; and the Delaware of Six Nations in Ontario. Lenape and other Indigenous Peoples, languages, and cultures continue to thrive in Lenapehoking and beyond.

American art institutions have long benefitted from and participated in settler colonialism. It is crucial that we work to address these harmful legacies. As the oldest art museum and school in the US, PAFA takes this work seriously, and commits to pushing back against settler colonialism in:

How our archival and collection materials are understood, presented, discussed, and expanded;

The policies and practices of our institution;

The administration and operation of our school;

How we design educational curricula and programming;

How we train and educate emerging artists; and

How we understand who is represented within and invited into the spaces we cultivate

PAFA is committed to tangibly and actively supporting Lenape and other Indigenous arts, cultures, sovereignty, and presence through our ever-developing exhibitions, residencies, programming, policies, and curricula. We invite everyone who engages with PAFA to honor these living communities and to work alongside us to foster ethically responsible futures for the American art world.

* This is a working statement and has not been approved by PAFA’s Board of Trustees

* As a living statement will continue to change over time as we continue to learn and build relationships.

Our Progress +

Our Progress +

When we were asked to craft an official territorial acknowledgement for the institution, we asked ourselves several tough, but important grounding questions:

Who owns this land?

How did this institution come to be here?

How has this institution participated, to this day, in colonization and settler colonialism, and in the ongoing erasure and dispossession of Indigenous peoples from these lands?

How can this institution do better?

-

We often hear — indeed, we often share — a celebratory narrative about PAFA being the oldest museum and art school in the country. This narrative includes a celebration of the many firsts that PAFA has had as a world renowned institution for art education, as well as PAFA's ability to create opportunities for women and African American artists. In celebrating those selected parts of our history, we often refrain from acknowledging the settler colonial and colonizing legacies of PAFA as the roots of this narrative: Benjamin West’s romanticized imagining of Penn’s Treaty with the Lenape is one of the most famous paintings in our collection. Thomas Penn, the very person who commissioned that piece, enacted atrocious violence for his role in the fraudulent Walking Purchase, which forcibly removed Lenape from this territory.

As we began to educate ourselves as an institution and deepen our understanding of the rich cultural heritage, traditions, and contributions of Indigenous peoples, it became clear to us that PAFA’s territorial acknowledgement had to be done responsibly, accountably, and in reciprocal relationship with the community whose land PAFA occupies. PAFA's first Land Acknowledgement Statement had to honor the presence of Indigenous communities, recognize the importance of ongoing relationship-building with Indigenous communities, affirm our commitment to reconciliation and healing, and actively support their initiatives and aspirations.

Land Acknowledgement Statements are a way to recognize and respect the Indigenous peoples on whose traditional territories our institutions are situated, and a gesture of respect towards the Indigenous communities that have stewarded these lands for generations, fostering a spirit of collaboration and partnership. They have become an institutional practice that holds great potential for meaningful engagement with Indigenous peoples and their histories and their contemporary realities. By incorporating Land Acknowledgement Statements into our institutional practices, we cultivate an environment that embraces diversity, inclusivity, and social justice.

PAFA's Land Acknowledgement Statement is but a small move towards confronting and contending with our individual, collective, and institutional complicities in settler colonialism, and to being accountable to our responsibilities in this Lenape territory — this ongoing, sovereign, and unceded Lenape homeland. Understanding the historical context faced by Indigenous communities is crucial in dismantling systemic inequalities, within the institution and throughout society.

We recognize that PAFA’s territorial acknowledgement must be more than mere words — that, indeed, it cannot simply be an acknowledgement. Rather, it must be a call-to-action that comes with long-term and ongoing relational accountabilities, and must include direct, tangible actions that involve centering Lenape voices, perspectives, and sovereignty.

We thank our PAFA community for their support and dedication to this vital project. Let us embark on this journey together and embrace the power of Land Acknowledgement Statements to transform our PAFA community.

Timeline

2019. PAFA begins its DEIB transformation

2020. PAFA’s Board of Trustees approves the Belonging Report, an action plan to inform and improve diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) support, policies, and practices at PAFA, and to advance PAFA’s core values as a community.

2019. PAFA’s Chief Operating Officer, Dr. Lisa Biagas, introduces a policy to replace Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples Day. This measure does not receive enough support from the PAFA community to move forward.

2022. In October 2022, PAFA held a one-hour online introductory workshop led by IPD Philly (Indigenous Peoples’ Day Philly Inc). This workshop provided participants the opportunity to learn about Indigenous histories, presence, and issues in Philadelphia and the US, and to begin developing concrete plans of action that will help support PAFA’s efforts to confront and challenge settler-colonial legacies.

2020. PAFA hires its inaugural Director of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging and Deputy Title IX Coordinator, Dr. Ronke Oke.

2022. PAFA officially observes Indigenous Peoples Day as an institutional holiday. Dr. Lisa Biagas charges Drs. Ronke Oke and Ashley Caranto Morford to craft an institutional Land Acknowledgment Statement.

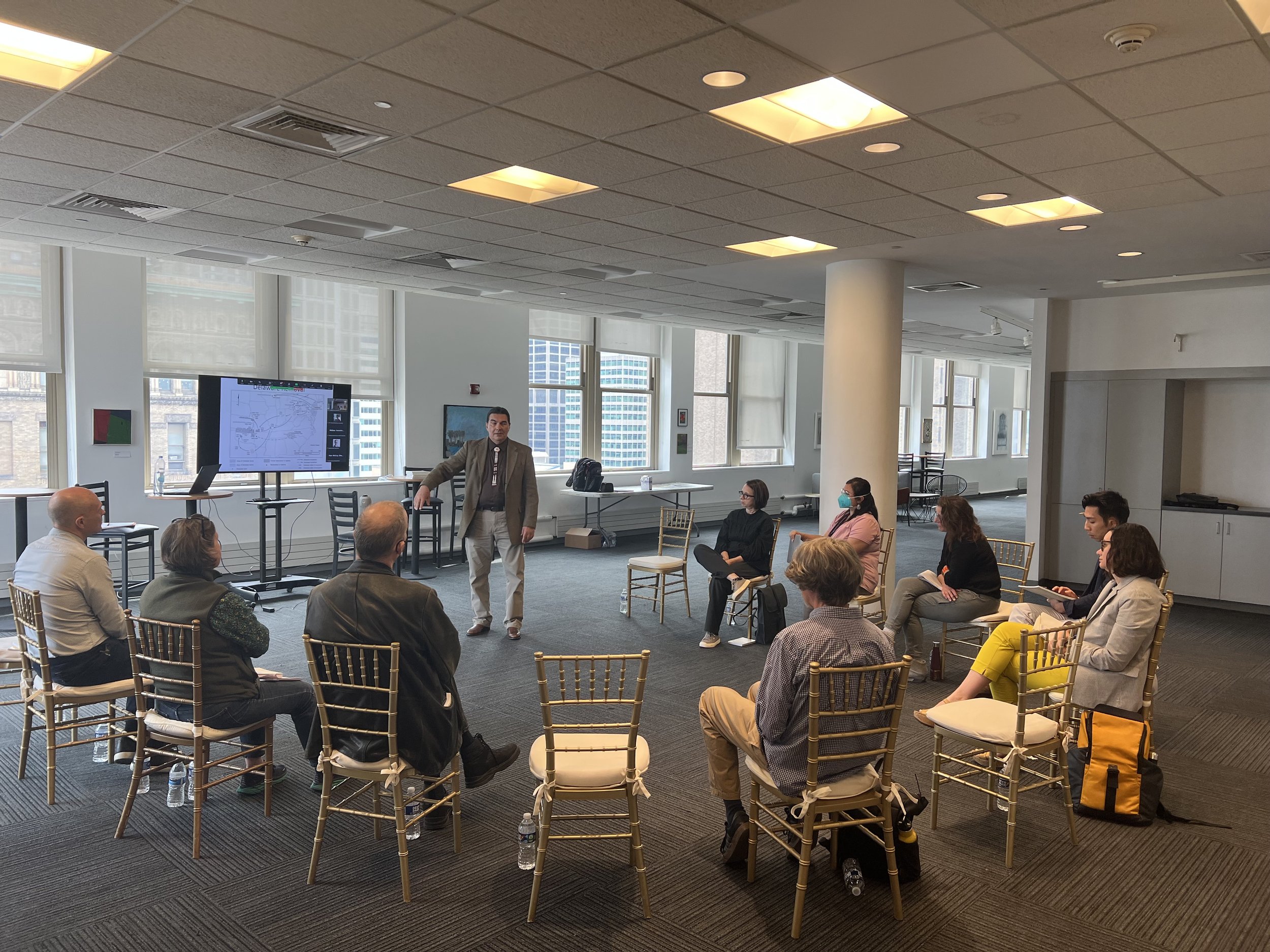

2023. In May 2023, PAFA held a Living Land Acknowledgement workshop facilitated by Curtis Zunigha from The Lenape Center. This workshop was the first step to ensure that PAFA’s territorial acknowledgement is done responsibly, accountably, and in reciprocal relationship with the community whose land PAFA occupies.

2023. After receiving consent from Lenape leaders, Drs. Ronke Oke and Ashley Caranto Morford begin crafting the first draft of PAFA’s Land Acknowledgment Statement.

2023. In July 2023, Drs. Ronke Oke and Ashley Caranto Morford incorporate stakeholder feedback into the working draft of PAFA’s Land Acknowledgment Statement.

2023. In August 2023, Drs. Ronke Oke and Ashley Caranto Morford finalized PAFA’s Living Land Acknowledgement (a working draft).

2023. We continue to welcome feedback from Lenape leaders and community members. This statement remains open to change, as it is a living part of our institution. We will add to the timeline as we continue to learn and build relationships.

2022-2023. Following the IPD, Philly Workshop, and based on Mia Mingus’ idea of accountability pods, Dr. Ashley Caranto Morford led a group of PAFA staff and faculty in a monthly meeting to develop, share, and strategize how PAFA can be responsible to Indigenous studies in a holistic way.

2022. Drs. Ronke Oke and Ashley Caranto Morford meet with Dr. Anna Marley (Chief of Curatorial Affairs) and Clint Jukkala (Executive Dean of the College) to gain more institutional support for a Living Land Acknowledgement Statement Workshop.

2023. In May 2023, Drs. Ronke Oke and Ashley Caranto Morford met with Lenape leaders to discuss the process of creating a meaningful and action-based territorial acknowledgement together, as a first step in beginning to build an ongoing relationship between the Lenape nation and the PAFA community.

2023. In April 2023, the first draft of PAFA’s Living Land Acknowledgment Statement is circulated to the OISE team, POD members, and participants from The Living Land Acknowledgment Workshop for feedback.

2023. Drs. Ronke Oke and Ashley Caranto Morford sent the Working Draft of PAFA’s Land Acknowledgement Statement to Lenape leaders and Curtis Zunigha for feedback.

2023. In September 2023, Drs. Ronke Oke and Ashley Caranto Morford launched this page on the OISE website so that the PAFA community and external stakeholders can track our development progress to date.

History of Lenape Land Dispossession

Settler colonialism cannot be reduced nor confined to a historical event (Wolfe, 1991). Rather, it is an ongoing structure and process — interlocked with other systems of oppression, including imperialism and capitalism — that is always transforming and unfolding (Wolfe, 1991). This timeline offers some key moments in the long and violent process of colonial states, governments, and settlers forcing Lenape Peoples from their homeland.

Since time immemorial: Lenapehoking — the lands and waters that New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware are currently on — has always been the territories of the Lenape Peoples.

-

1626: Dutch colonialists swindled land from the Lenape in what settlers commonly refer to as the “purchase of Manhattan” and re-named this area New Amsterdam (Zunigha, 2022, p. 42). The Dutch colonialists built a fort and a wall to keep the Lenape out (p. 42), and the Lenape experienced massacres and violence from colonialists during Dutch colonization of Lenapehoking. In 1664, the British took colonial power in the region over from the Dutch (p. 43).

-

1682: Chief Tamanend of the Lenape and the Governor of the British colony of Pennsylvania, William Penn, made an agreement that Penn’s colony could peacefully occupy Lenape land in what is today Philadelphia (p. 44).

1737: Through the fraudulent Walking Purchase, Pennsylvania authorities swindled hundreds of thousands of acres of Lenape land, forcing the Lenape west out of their homeland (p. 44). Many Lenape became refugees in the Haudenosaunee territory of the Susquehanna Valley (p. 45).

1756: Amidst the Seven Years’ War and French and British settler colonial powers fighting one another, the Lenape continued to resist and refuse colonial subjugation. In response to this resistance, Pennsylvania Deputy Governor Robert Morris enacted a scalp bounty that directly targeted the Lenape (p. 46). This brutal atrocity forced the Lenape to relocate again, with some community members moving to the Tuscarawas River Valley in Ohio, some moving north along the Susquehanna River, and some moving into Ontario, Canada (p. 48).

1760s: As settlers moved in large numbers into the Delaware and Susquehanna River Valleys, many Lenape moved to Fort Pitt (what is today Pittsburgh) but, in 1765, in the aftermath of ongoing British warfare, they were forced to relocate even further west (p. 49).

-

1778: The Lenape signed the Treaty at Fort Pitt, a military alliance with the new United States. This was the first treaty between Indigenous Peoples and the U.S. (p. 50). Through this alliance, it was agreed that the Lenape would help the U.S. in their fight against the British, the U.S. would honor and recognize Lenape sovereignty and territorial rights, and the two nations would have a peaceful relationship moving forward (Zotigh, 2018, par. 5-8).

1782: Despite the Treaty of Fort Pitt, when the U.S. defeated the British in the Revolutionary War, American settlers continued to settle ever westward and take more land. Lenape people were massacred in the process, and this violence led many Lenape to flee the area they were living in yet again (Zunigha, 2022, p. 51-2).

1792: As the U.S. formed the colonial states of Michigan and Indiana with the Passage of the Northwest Ordinance in 1787, Lenape communities were made to cross into Ontario, Canada. This relocation saw the establishment of the Delaware Nation at Moraviantown, Ontario, which continues to thrive today (p. 52). At the same time, the U.S. government dictated that only the U.S., and not Indigenous Peoples, could sell surplus land, and that Indigenous Peoples could not own land, they could merely occupy U.S.-owned land (p. 52).

1795: Indigenous Peoples continued to resist colonial subjugation and conquest. In the aftermath of the Battle of Fallen Timbers (near current day Toledo, Ohio), in which various tribes fought against but were defeated by U.S. General “Mad Anthony” Wayne, twelve Indigenous nations signed the Treaty of Greenville. Under this treaty, they were made to forcibly cede Eastern Ohio, and the Lenape were once again pushed further west (p. 53). By 1800, many Lenape were living along the west fork of the White River in Indiana in the territory of the Miami (p. 53).

1812: During the American War of 1812 with Great Britain, the Lenape chose to remain neutral in taking sides, and, pleased with this stance, the U.S. government relocated the Lenape in the White River area to an American fort at Piqua (Ohio) for protection (p. 55). After the war, this group of Lenape returned to White River (p. 56).

1818: The Lenape signed the Treaty of St. Mary’s in Ohio and were forced west of the Mississippi River as settlers continued to push westward (p. 56). The U.S. government gave the Lenape two reservations in Missouri, but the land – with its rockiness, poor hunting, and flooding – was inadequate (p. 56). While some Lenape petitioned to move to Kansas, others went to Texas (then part of Mexico) while others had moved to Wisconsin (p. 57).

1829: Through another treaty by the U.S. government, many Lenape moved again, this time to reside in Kansas (p. 57).

1866: The Lenape residing in Kansas were forced to sign a treaty with the U.S. giving up their reservation in Kansas, because railroad barons wanted access to this land as they expanded their enterprise (p. 58).

1867: The Articles of Agreement between the Lenape and Cherokee established a Lenape community in Cherokee territory in Oklahoma. This Lenape community remains in Bartlesville, Oklahoma today (p. 58).

1877: The Lenape who had gone to Texas came to reside in Anadarko, Oklahoma, where they continue to this day (p. 57).

Present-day: Today, because of the ongoing history of colonization, many Lenape live in diaspora outside of their homeland: the Delaware Nation in Anadarko, Oklahoma; the Delaware Tribe of Indians in Bartlesville, Oklahoma; the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians in Wisconsin; the Munsee-Delaware Nation in Ontario; the Delaware Nation at Moraviantown in Ontario; and the Delaware of Six Nations in Ontario. They remain deeply connected to their culture and homeland, and they are continuing to fight to return to Lenapehoking, the territory that has been their home since time immemorial.

-

Wolfe, Patrick. 1991. Settler Colonialism and the Transformation of Anthropology: The Politics and Poetics of an Ethnographic Event. London: Cassell.

Zotigh, Dennis. 2018. “A Brief Balance of Power — The 1778 Treaty With the Delaware Nation.” Smithsonian Magazine. Accessed 20 August 2023. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/blogs/national-museum-american-indian/2018/05/22/1778-delaware-treaty/.

Zunigha, Curtis. 2022. Lenapehoking: An Anthology. Edited by Joe Baker, Hadrien Coumans, and Joel Whitney. Brooklyn: Ugly Duckling Presse. pp. 41-59.

Resources

-

Territorial vs Land Acknowledgement: Territorial and land acknowledgements seek not only to recognize the Indigenous lands that individuals and institutions are gathered/built on and nourished by, but to also reflect on responsibilities that individuals and institutions have to the Indigenous lands and life of that territory. The term territorial seeks to emphasize that water is included in land and land-based responsibilities.

Federally Recognized Tribes vs State Recognized Tribes: As UCLA’s Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Office (2020) details, “Federal recognition is the ‘legal acknowledgement’ of the sovereign and separate political status of tribal nations by the U.S. Federal government. It establishes a political and legal relationship between an Indian tribe and the U.S., which carries particular rights and responsibilities for both parties, potentially entitling tribes to certain federal resources that trigger the operation of an entire body of Federal law [...] There are currently 574 federally recognized American Indian and Alaska Native tribes and villages.” State recognition is different. “There are 14 states that have recognition processes for American Indian tribes, usually through legislative processes. Currently, there are more than 60 state-recognized tribes in 11 states. While this is an important recognition of inherent sovereignty,” unlike federal recognition, “state recognition does not confer upon the tribes and their members legal status as American Indian Tribes under U.S. law.”

Unrecognized Tribes: Currently, Pennsylvania does not recognize any Indigenous nations federally or at the state level. But just because an Indigenous nation is not officially recognized through federal or state recognition does not mean that it is not a valid Indigenous nation. The politics surrounding which nations have been recognized and which have gone unacknowledged is rooted in colonization and settler colonialism. Many Indigenous nations are currently petitioning for official forms of recognition, but the process of seeking federal recognition is arduous, expensive, and can take many decades.

Indigenize: The ongoing and dynamic process of centering, respecting, and celebrating Indigenous worldviews, perspectives, voices, and visions. In an institutional and educational setting, this process should occur at every level and in every practice and procedure of the institution, from policy to curriculum development to syllabi creation.

Decolonize: According to Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang in their article “Decolonization is not a metaphor” (2012), decolonization in the context of North America must center the concrete, material, and tangible restitution of Indigenous lands and life to Indigenous Peoples. As they write, “Decolonization brings about the repatriation of Indigenous land and life; it is not a metaphor for other things we want to do to improve our societies and schools” (p. 1).

Settler colonialism: Through processes of settler colonialism, colonialists arrive in and take over Indigenous lands with the intention of settling permanently and replacing by displacing, dispossessing, and ultimately erasing and eradicating, enacting genocide against, the sovereign Indigenous nations and populations of those lands, who have lived in those lands since time immemorial. Canada, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand are just a few examples of settler colonial regimes.

Lenape: The Lenape Peoples make up the Indigenous nations whose homelands are Lenapehoking, a large territory currently colonially occupied by New Jersey and parts of New York, Pennsylvania, and Delaware. Many Lenape were forcibly removed from their homelands through the violence of colonization, and now reside in Oklahoma, Wisconsin, and Southern Ontario (Canada): these Lenape nations are the Delaware Nation (Anadarko, Oklahoma), the Delaware Tribe of Indians (Bartlesville, Oklahoma), the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians (Wisconsin), the Munsee-Delaware Nation (Ontario), the Delaware Nation at Moraviantown (Ontario), and the Delaware of Six Nations (Ontario). State-recognized Lenape communities in New Jersey and Delaware include the Lenape Indian Tribe of Delaware, the Nanticoke-Lenni Lenape Tribal Nation, and the Ramapo Munsee Lenape Nation.

The Walking Purchase of 1737: This was a fraudulent purchase, a land swindle, enacted by the Penn family and Pennsylvania authorities against the Lenape, which forcibly removed the Lenape from their homelands. As the Delaware Tribe of Indians details on their official website, “In order to convince the Lenape to part with the land, the Penns falsely represented an old, incomplete, unsigned draft of a deed as a legal contract. They told the Lenape that their ancestors some fifty years before had signed this document which stated that the land to be deeded to the Penns was as much as could be covered in a day-and-a-half’s walk. Believing that their forefathers had made such an agreement the Lenape leaders agreed to let the Penns have this area walked off. They thought the whites would take a leisurely walk down an Indian path along the Delaware River. Instead, the Penns hired three of the fastest runners, and had a straight path cleared. Only one of the ‘walkers’ was able to complete the ‘walk,’ but he went fifty-five miles. And so by means of a false deed, and use of runners, the Penns acquired 1200 square miles of Lenape land in Pennsylvania, an area about the size of Rhode Island!” (2013).

Treaty of Shackamaxon: A living treaty made between William Penn and Lenape Chief Tamanend, wherein settlers and the Lenape agreed to live peacefully within these Lenape lands together. Anyone who lives in this territory has the responsibility to respect and uphold this treaty.

Indigenous sovereignty: Indigeneity cannot simply be subsumed into the concept of race. Importantly, Indigeneity is a political designation. Indigenous Peoples are sovereign peoples with their own governance systems distinct and separate from colonial nations like the US and Canada. When we talk about Indigenous sovereignty, we are talking about Indigenous Peoples’ ongoing right to govern themselves.

Land rights: Indigenous Peoples have been caring for and continue to share strong relationships with and knowledge about their homelands. Indigenous Peoples have never surrendered their lands. And, within Indigenous worldviews, land cannot simply be defined and understood though the Western concept of property and ownership. Land is a living relation, a collective responsibility, and is deeply part of culture, kinship, governance systems, and more. In short, land is a crucial part of Indigenous sovereignty. Indigenous rights and title speak to and recognize the inherent and collective rights of Indigenous Peoples to their lands, including the right for Indigenous Peoples to continue the practices that they have held on the land since time immemorial and the need for Indigenous nations to provide free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) for any projects to be constructed on and that may impact their lands.

Indigenous Peoples: To refer to Indigenous Peoples as a Peoples is to recognize their distinct sovereignties and nationhoods. Further, to refer to Indigenous Peoples in the plural also recognizes that there are many different distinct Indigenous nations.

Indigenous as a proper noun: In the words of Cherokee scholar Daniel Heath Justice, “The capital ‘I’ [...] affirms a distinctive political status of peoplehood, rather than describing an exploitable commodity, like an ‘indigenous plant’ or a ‘native mammal.’ The proper noun affirms the status of a subject with agency, not an object with a particular quality” (Why Indigenous Literatures Matter, p. 6)

-

Executive Sponsorship: Identify a Senior Leader to sponsor the initiative

Buy-In: Obtain institutional buy-in from Senior Leadership

Lenape Leadership: Connect with and invite Lenape community and leaders.

Meet with Lenape leaders to build relationship and to seek permission

Training: Host a Living Land Acknowledgement Workshop

Vision: Collaborate with Lenape leaders to envision a long term plan of action on the part of PAFA

Workshop action items with PAFA’s administrative leadership

Report Out: Report back to Lenape leaders

Draft: Collaborate with Lenape leaders to draft PAFA’s Living Land Acknowledgement Statement

Get institutional buy-in from PAFA’s constituency groups (faculty, staff, senior leadership, board members)

Collaborate with Lenape leaders to revise PAFA’s Living Land Acknowledgement

Finalize PAFA’s Living Land Acknowledgement

Board Approval of Living Land Acknowledgement statement

Policy: Codify the Living Land Acknowledgment

Normalize the Living Land Acknowledgment by creating policies governing: use, placement on the website, ceremonies, and institutional events

Keep it Living: Determine how PAFA will keep checking in to address key action plan and keep it ongoing

-

The Lenape Center: https://lenape.center/

The Lenape diaspora, once on the brink of erasure, championed in New York exhibition: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/01/24/lenape-diaspora-exhibition-brooklyn-public-library-lenapehoking

Google Arts and Culture: Lenapehoking: https://artsandculture.google.com/story/gwWxsh46HWIlsQ

‘Tourists’ in Our Own Homeland: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/lenape-people-lenapehoking_n_628e542ee4b0cda85db9420c

FAQs

-

The term decolonization refers to the removal or undoing of colonial elements. The term indigenization moves beyond tokenistic gestures of recognition or inclusion to meaningfully change practices and structures.

For more information, see Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang’s article, “Decolonization is not a metaphor” Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang

-

According to The Treaty of Shackamaxon, the territories that became Delaware and Pennsylvania were never given away by the Indigenous communities who inhabited the land before European settlers. They were stolen by the Penn family (See The Walking Purchase of 1737). For these reasons, the territories of Delaware and Pennsylvania remain the ownership of the Lenni-Lenape people, the original inhabitants of this land.

-

The term territorial helps to emphasize and make clear that land includes the full diversity of a geographical space, including, importantly, water. The term call-to-action emphasizes that there is an active component to recognizing the territory we are on.

Curtis Zunigha (The Lenape Center) gave the following example to explain the difference between acknowledgement and call to action and the importance of territorial call-to action statements: (paraphrased below):

Imagine you are about to drink a bottle of water and someone comes behind you and snatches it out of your hand. After some time, they say that they “acknowledge they are not the owners of the water bottle and that they realize they forcibly stole your water bottle. Then they open the cap and begin to drink the water.”

It is not enough to simply acknowledge the wrongdoing. Actions to write the wrong are equally vital.

According to Chelsea Vowel, the “intended purpose of territorial acknowledgements is recognition as a form of reconciliation.” This goes further than merely recognizing the presence of Indigenous people and communities; it also enumerates, through admission, the deep and long history of forced removal and the violent relationship between settlers, settler institutions and Indigenous communities.

Land acknowledgement statements are intentionally repetitive in order to disrupt the spaces the words are offered into. Territorial call-to-actions (CTAs) require individuals and institutions to ask what must be done and what is required from us? CTAs require individuals and institutions to take concrete and direct action to be accountable.

For more information, see Chelsea Vowel’s writings on “Beyond the Territorial Acknowledgement”

This was a collective effort.

We would like to thank Lenape leaders from the Delaware Tribe of Indians, Delaware Nation at Moraviantown, and Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohicans for giving their consent to PAFA to draft our territorial acknowledgement statement.

We would also like to thank Curtis Zunigha from The Lenape Center for his partnership and generosity throughout this process.

We thank our PAFA community for their support and dedication to this vital project.